A good friend of mine, Hilla, is an accomplished musician and composer. She does an 8th-Century Anglo-Saxon persona – a time of relative freedom for women, and interesting things happening in the realm of story, poetry, and song. We worked out a barter: she would compose a song for my repertoire, and I would make a new overdress for her. She delivered her part last spring; I, however, took a bit longer. But it’s finally done!

The Anglo-Saxon women’s costume from this period is a marvel of simplicity and practicality. Worn over a long basic tunic, it’s essentially two large rectangles sewn together at the sides from mid-rib-cage to just above the ankle. The top is folded over in front and back, and pinned at the fold on top of each shoulder. The peplum thus created can be pinned along the arms as well, or the back brought up and over the shoulders in a shawl fashion for extra warmth. A single such garment will fit a multitude of different body shapes and sizes; the length is adjusted by the amount folded over, as well as by blousing the midsection over the belt which snugs it in and carries her pouch, belt knife, etc. The lack of tailoring also reduces fabric waste, important when every thread was spun by hand and laboriously woven; with no cuts for shaping, the dress can later be taken apart and re-purposed if parts become worn or irremediably soiled. It can even be unpinned and used as a blanket at need!

The Anglo-Saxon women’s costume from this period is a marvel of simplicity and practicality. Worn over a long basic tunic, it’s essentially two large rectangles sewn together at the sides from mid-rib-cage to just above the ankle. The top is folded over in front and back, and pinned at the fold on top of each shoulder. The peplum thus created can be pinned along the arms as well, or the back brought up and over the shoulders in a shawl fashion for extra warmth. A single such garment will fit a multitude of different body shapes and sizes; the length is adjusted by the amount folded over, as well as by blousing the midsection over the belt which snugs it in and carries her pouch, belt knife, etc. The lack of tailoring also reduces fabric waste, important when every thread was spun by hand and laboriously woven; with no cuts for shaping, the dress can later be taken apart and re-purposed if parts become worn or irremediably soiled. It can even be unpinned and used as a blanket at need!

Hilla’s persona is of at least the middle nobility, due to her educational level and skillset. This allowed me a bit more freedom in choice of color and decoration for her dress. People of higher societal class were more likely to wear more and brighter colors than those of lower class and wealth. Linen and wool fabrics were both typical of the time, so I chose linen as being more comfortable in warm weather and somewhat easier to care for than modern wools. The colors are acceptably close to those possible with dyestuffs of the time – the rust color coming from iron oxide, the green possible as an overdye of woad with yellow plant-based dyes, and the band of light tan coming from any of a number of sources. The dress is entirely hand-sewn.

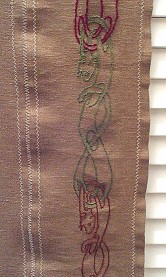

The first step was the embroidered band. The design draws heavily on the interlaced zoomorphics seen in both Pictish and Norse carvings of the period; while Norse costume was not usually heavily embroidered, it’s reasonable to think that such designs on trade items might have made their way to English shores where such decoration was indeed known.

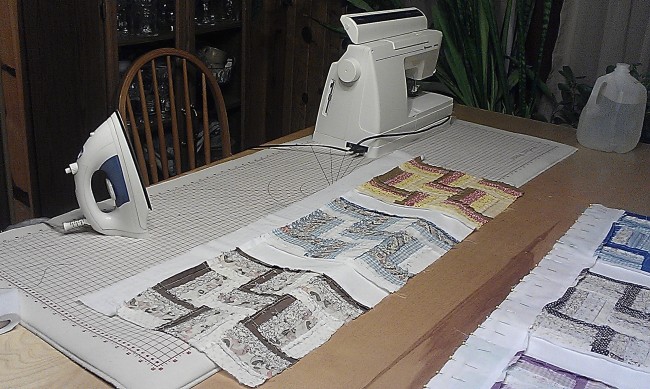

finished bands before separation

I used a French lambswool colored with natural dyes for the embroidery. In the photo to the right, you’ll see that I basted together both lengths of the band in order to keep the color pattern consistent; this also kept the band from being stretched out of shape on the slate-style embroidery frame that I used for it. (The slight rippling along the basting disappeared as soon as the bands were separated.) The pattern was traced onto clear Sulky wash-away stabilizer for ease of transfer. All of this section is done in stem stitch with a single, un-split thickness of the wool. All told, it’s approximately 104″ long by 3″ finished width.

buttonhole stitching along the upper edge of the embroidered band

Once the bands were finished and the stabilizer removed (including a pass through the wash – gentle cycle, in a mesh bag, and hung to dry – to remove any last remnants), I attached it to the main body of the dress. I then added the stripe of green linen, which is actually wide enough to cover the entire back side of the embroidery to protect it. After sewing the bottom edge of the embroidered band down to the green band, I used more wool in a buttonhole stitch both as an embellishment and to keep the seams flat.

I then sewed the side seams. I planned to finish all raw edges to prevent fraying; since the top is folded over, both sides of the seam would be visible and thus needed to be cleanly finished. This meant turning them under and catch-stitching them as invisibly as possible.  Basting the sides together all the way from top to bottom allowed me to press in a neat, even seam allowance that became the hems for the areas left open. (It also made it much easier to align the color bands correctly.) I had considered embroidering along the seams as well, but decided instead to leave them as inconspicuous as possible.

Basting the sides together all the way from top to bottom allowed me to press in a neat, even seam allowance that became the hems for the areas left open. (It also made it much easier to align the color bands correctly.) I had considered embroidering along the seams as well, but decided instead to leave them as inconspicuous as possible.

The completed dress then received a final washing – again, gentle cycle – and was hung to dry. Linen handled this way needs little or no ironing and will last quite a long time.

Hilla and I are both very happy with the final product!

Last August, I was invited to contribute a dessert recipe to Protea Wine’s blog. It was an adaptation of something that had been floating around the Internet for a few weeks, that I’d brought into the office one day to rave reviews. I’d fully intended on posting it here, but then lost track of it…until I just recently stumbled across the image files again.

Last August, I was invited to contribute a dessert recipe to Protea Wine’s blog. It was an adaptation of something that had been floating around the Internet for a few weeks, that I’d brought into the office one day to rave reviews. I’d fully intended on posting it here, but then lost track of it…until I just recently stumbled across the image files again. Bars:

Bars:

reciprocating saw to slice through the rails in 3-foot sections (the max size for our city bulk-waste site to accept) before pulling them off the posts. I have to say that whoever built that fence intended it to stay where it was…there were some pretty major nails securing it to the posts! We also stained the posts while they were exposed.

reciprocating saw to slice through the rails in 3-foot sections (the max size for our city bulk-waste site to accept) before pulling them off the posts. I have to say that whoever built that fence intended it to stay where it was…there were some pretty major nails securing it to the posts! We also stained the posts while they were exposed.